A fallacy is a mistake or misunderstanding in logic that fails to support one’s argument. It’s a key aspect of critical thinking , and it can help you to avoid falling prey to fake news . If you’re taken in by logical fallacies, false conclusions might cause you to make decisions that you later regret.

Also, using a logical fallacy in your own arguments can make you look gullible or uninformed. When trying to make an argument, it’s important for the logic behind your argument to make sense. If you make an error in logic, this can undermine your argument and leave you with little else to back up your claim.

While it is true that all fallacies are faulty inferences, each fallacy is different and knowing the name and pattern of each can clarify your thinking, improve your debating skills, and help you better discover truth.

Logical fallacies play a huge role in how people think and in how they communicate. Here are common logical fallacies you may encounter during an argument or debate:

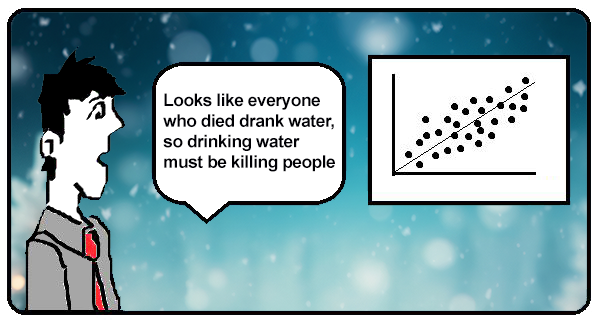

1. The correlation/causation fallacy

When people believe that correlation equals causation. Oftentimes, correlations happen by coincidence or outside forces. They don’t necessarily mean that one thing is directly causing the other.

Example: “Our website got a lot of new traffic last week. We also changed the font on our website last week. So our new font is the reason we got more website views.”

2. The bandwagon fallacy

The bandwagon logical fallacy (or ad populum fallacy) occurs when we base the validity of our argument on how many people believe or do the same thing as we do. In other words, we claim that something must be true simply because it is popular. This fallacy is based on the idea that if many people agree on the same point, it must be true. Believing this kind of fallacy can make you susceptible to peer pressure.

Example: “Everyone is happy with our company’s policies. This means that there is no need to get feedback from our new employees.”

3. The anecdotal evidence fallacy

Rather than using hard facts and data, people using the anecdotal evidence fallacy base their arguments on their own experiences. These kinds of arguments focus on emotions over logic. While something may be true to this one person, it may not apply to the general population.

Example: “Whenever I use our email system, I always experience glitches. I think we need to replace the entire system for the company.”

4. The straw man fallacy

The straw man fallacy is an argument that is thin and has no substance. It occurs when your opponent argues against a position you aren’t even trying to present. The straw man logical fallacy is the distortion of an opponent’s argument to make it easier to refute. By exaggerating or simplifying someone’s position, one can easily attack a weak version of it and ignore their real argument.

Example:

Person A: “I think that George is a talented copywriter and should be promoted.”

Person B: “So what you’re saying is that all of our other copywriters are untalented? That kind of attitude is hurtful to our team.”

Person 1: “I think we should legalize marijuana.”

Person 2: “So you are fine with children taking ecstasy and LSD?”

Explanation: In this example, Person 1 never suggested that it’s fine for children to do drugs. Person 2 takes the original argument to its logical extreme and creates an absurd, easy-to-defeat argument.

Person 1: Unequivocally, the Earth is round. Countless observations have been made along with countless measurements proving that the Earth is indeed round.

Person 2: You’re not much of a free thinker are you? Your years of schooling, indoctrination as I like to call it, are clouding your judgment. Do you really believe NASA doesn’t manipulate the images to suit their agenda? The Earth is definitely flat.

Explanation: Person 2 has distorted what Person 1 said to a degree that is almost laughable. Nowhere in Person 1’s statement did he/she mention anything about NASA or the formal education system. The term “free thinking” is often used by individuals who embrace conspiratorial thinking in an attempt to rationalize holding a fringe view that is typically unsupported by any evidence. Person 2 has blatantly committed a straw man fallacy.

5. The false dilemma fallacy

This fallacy argues that you can break all arguments into two opposing views. The reality is that most subjects have a spectrum of views and opinions. Rather than assuming an issue is clear-cut between two arguments, they typically are more fluid and nuanced. The main drawback of this kind of fallacy is that it makes the other party look unreasonable. Instead of trying to compromise, those using this kind of argument try to make their opponent look more extreme.

Example: “If our competitor believes in this cause, then it must be wrong. We should avoid supporting this cause since their ideals are so different from ours.”

6. The slothful induction fallacy

People use the slothful induction fallacy when they ignore substantial evidence and make their claim based on a coincidence or something entirely irrelevant.

Example:

Person A: “I was excited to see that our onboarding process increased our employee retention rates. When I interviewed our employees last week, 98% of them said they are still with the company because of the support they got when they first started.”

Person B: “I think the real reason everyone likes it here is that we allow dogs in the office.”

7. The hasty generalization fallacy

When someone comes to a conclusion based on weak evidence, they are using the hasty generalization fallacy. Those using this argument fail to use well-researched and proven evidence to make their claims. Hasty generalization or the fallacy of stereotypes is making assumptions about a whole group or range of cases based on a sample that is inadequate.

Example: “Librarians are shy and smart” “Wealthy people are snobs” “Aleksi learned a lot from our last company retreat. We need to spend a large portion of our budget sending our entire company on annual retreats so that we can all learn.”

8. The middle ground fallacy

Those using this kind of argument believe that finding a compromise between two contrasting points must be the right solution. What they may not realize is that there may be better solutions that are entirely unrelated to those two opposing arguments.

Example: “I think our employer should raise our salaries while Jenny thinks they should stay the same. To compromise, our employer is giving us a small end-of-the-year bonus.”

9. The burden of proof fallacy

The burden of proof fallacy is when you assume something is true simply because there is no evidence against it. Those using this argument claim that their ideas and opinions are correct because they cannot find any other sources that oppose what they have to say.

Example: “Everyone loves our marketing campaign because I haven’t heard anyone say otherwise.”

10. The no true Scotsman fallacy

This fallacy is when one person protects their generalized claim by denying counterexamples. They do this by changing the initial terms of their generalization to invalidate any counterexamples that might exist.

Example:

Person A: “Every writer loves using the Oxford comma.”

Person B: “Well, actually, many writers who follow AP style do not use the Oxford comma.”

Person A: “Then writers who use AP style must not be true writers.”

11. The Texas sharpshooter fallacy

This fallacy gets its name from a story where a man shoots his gun at a wall and draws a target around the bullet holes afterward. He then shows people the target to prove that he has excellent aim. Essentially, this fallacy is when you pick specific evidence or data that fits your claim while ignoring the rest of the information you have. Researchers often need to be careful about only picking sets of data that support their hypothesis when they should be looking at everything they collected.

Example: “Jeremy claims he is a successful businessman because he landed five new clients this month. What he fails to mention is that his sales are down 50% this year.”

12. The tu quoque fallacy

Rather than coming up with a valid counterargument, those using the tu quoque fallacy invalidate their opponent’s criticisms by addressing them with another criticism. With this kind of argument, you find a way to attack your opponent instead of coming up with a logical reason to argue against their original claim.

Example:

Person A: “I think you need more project management experience before you can qualify for this promotion.”

Person B: “You don’t even have any project management experience, so who are you to make this claim?”

13. The personal incredulity fallacy

When people find it challenging to understand why or how something is true, they may use this argument to claim it is false. Even if a large group of people agrees that they find it challenging to believe something is true, this doesn’t automatically mean it is false. It may simply mean that they need more context or information to fully understand the claim.

Example: “I don’t understand how social media engagement is benefiting our brand, so I’m only going to focus on traditional forms of marketing.”

14. The appeal to authority fallacy

When people misuse authority, this kind of fallacy can occur. Those who use this fallacy often put too much confidence into one person’s opinions or thoughts. This is especially evident when this person is arguing something outside of their expertise.

Example: “Our CEO says we don’t need to worry about climate change, so I no longer need to find out ways for our company to be more sustainable.”

P1: Peter purchased a home successfully.

P2: Peter says that interest rate cap is a good option.

C: Therefore, interest rate cap is a good option.

15. The fallacy fallacy

While logical fallacies can undermine your argument, they don’t necessarily render your claims untrue. A fallacy fallacy is when someone notices your argument contains a fallacy, which leads them to believe your entire claim is false. Even if someone has a weak argument, you can still find that their point is true.

In the example below, the first person uses a fallacy to show that dogs are good companions. The second person uses the fallacy to prove them wrong. The third person explains that even though the first person is using a fallacy to support their claim, there actually is proof that dogs make good companions.

Example:

Person A: “Dogs are great companions because I love them.”

Person B: “Well, it’s clear to me that you are using the anecdotal evidence fallacy to prove your point. Due to this, I find it hard to believe that dogs make good pets.”

Person C: “While they are using that fallacy, there is plenty of hard evidence that does prove that does are good companions.”

16. Red herring logical fallacy

The red herring fallacy is the deliberate attempt to mislead and distract an audience by bringing up an unrelated issue to falsely oppose the issue at hand. Essentially, it is an attempt to change the subject and divert attention elsewhere.

Red herring fallacy example:

“In regard to my recent indictment for corruption, let’s be clear about what’s really important: unemployment! We really need to focus on creating jobs, and under my 10-point plan, here’s what we can achieve …”

Politicians often try to avoid difficult questions (e.g., on their own shortcomings) by raising an important but irrelevant issue like unemployment.

17. Slippery slope logical fallacy

The slippery slope logical fallacy occurs when someone asserts that a relatively small step or initial action will lead to a chain of events resulting in a drastic change or undesirable outcome. However, no evidence is offered to prove that this chain reaction will indeed happen.

Slippery slope logical fallacy example:

“The government should not prohibit drugs. Otherwise, the government would also have to ban alcohol and cigarettes. And then sugar and junk food would have to be regulated too. Next thing you know, the government would force us to exercise every day! In the end, the government would control every aspect of our lives!”

18. Hasty generalization logical fallacy

The hasty generalization fallacy (or jumping to conclusions) occurs when we use a small sample or exceptional cases to draw a conclusion or generalize a rule.

Hasty generalization logical fallacy example:

“My father smoked four packs of cigarettes a day from age 14 and lived until the age of 95. So smoking really can’t be that bad for you.”

19. Oversimplification fallacy

Oversimplification fallacy reduces the cause of an event to a single incident or phenomenon, even when an event has many causes.

Oversimplification fallacy example:

“I water the garden every day, which is why it grows so well.”

Watering the garden is certainly one cause of its growth, but the soil quality, amount of sunlight, and number of pests in the area are also major causes.

20. Bulverism fallacy

The logical fault of Bulverism is actually a form of the genetic fallacy. So its logical problem is really not new. It dismisses an opponent’s arguments because of their origins.

Bulverism fallacy example:

Father: Two sides of a triangle would always be greater in length than the third.

Mother: Oh you say that because you are a man.

20. Ad hominem fallacy

Attacking opponent’s personal traits or achievements to undermine their argument.

Example:

Henry is talking to his group of friends about how not only are vaccines especially effective at preventing disease, but they are also immensely safe as well according to science. Following Henry’s remarks, one of his friends comments:

P1: Henry got a C on his Chemistry test last week.

P2: So, he clearly doesn’t understand science well and is wrong here about the science.

Some other logical fallacies

https://web.cn.edu/kwheeler/fallacies_list.html

Some other cognitive Biases

- Gambler’s Fallacy: Believing that past events influence future events in games of chance.

- Base Rate Fallacy: Judging the likelihood of a situation by not considering all data.

- Pygmalion Effect: Believing that higher expectations lead to an increase in performance.

- Barnum Effect: Believing generic information is specifically tailored to oneself.

- Bottom-Dollar Effect: Disliking purchases that exhaust remaining budget.

- Bye-Now Effect: Mistaking the word “bye” for “buy” and paying more as a result.

- Butterfly Effect: Simple actions yield large rewards.

- IKEA Effect: Valuing something more if one has made it themselves.

- Halo Effect: Overall impression influences feelings about a brand or product.

- Dunning-Kruger Effect: People with low ability overestimate their competence.

- Occam’s Razor: The simplest solution is often the best one.

- Mandela Effect: Large groups remember an event differently from reality.

- Crowding-Out Effect: Public sector spending reduces private sector spending.

- Ringelmann Effect: Individuals become less productive as group size increases.

- House Money Effect: Investors take higher risks with reinvested capital than with initial investment.

- Snowball Effect: Any action evolves from something small to something significant.

- Hawthorne Effect: People work harder/perform better when they know they are being observed.

Frequently asked questions

If you’re speaking with someone who’s using logical fallacies, the first step is to identify the tactic clearly. It’s vital that you understand the different types of fallacies and why they invalidate an argument. Then, you can explain your opponent’s fallacy to them and to the rest of the audience uing examples or analogies. In some cases, it may be helpful to calm the audience’s emotions rather than using logical proofs.

When we speak with or listen to others, we can be subject to persuasion. This is why it’s important to think carefully about the arguments you say or hear. Learning to identify logical fallacies is a good way to improve your critical thinking and avoid erroneous opinions.

Learn to distinguish logical arguments from rhetorical arguments. If someone is trying to manipulate your emotions, it’s a good sign that their arguments could be false. Take note if the speaker uses bad proofs, lacks evidence, make false comparisons, or uses ignorance as proof of their conclusions.