Observing people and situations is an incredibly valuable tool. It gives you the ability to notice subtle cues during conversations, job interviews, presentations, and anywhere else so you can react to situations more tactfully. These are the trademark tools of Sherlock Holmes, as well as modern-day detectives you see on TV shows like Psych, Monk, or The Mentalist.

[Sherlock Holmes, and his biographer Dr. John Watson, inhabited 4 novels and 56 short stories written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle between from the years 1887 to 1927. ‘By a man’s finger-nails, by his coatsleeves, by his boots, by his trouser-knees, by his callosities on his forefinger and thumb, by his expression, by his shirt-cuffs-by each of these things a man’s calling is plainly revealed,” says Mr. Holmes.]

The two core values of Holmes’ skills are simple: observation and deduction.

Deductive reasoning/thinking is a form of verbal or conceptual argument related to logic and reasoning. Deductive reasoning often employs, Syllogism to achieve its goal. Syllogism is a logical argument made up of a major premise, a minor premise, and a conclusion. Sherlock Holmes’s extraordinary talent for a deduction has been well documented by Arthur Conan Doyle. Though they often seem nearly mystical in origin, Sherlock Holmes’s deductions were in fact the product of a keenly trained mind.

“I knew you came from Afghanistan…”

- A gentleman of a medical type, but with the air of a military man = clearly an army doctor.

- His face is dark, wrists are fair; this is not the natural tint of his skin = He has just come from the tropics.

- He has got a haggard face = He has undergone hardship and sickness.

- He holds his left arm in a stiff and unnatural manner = He got his left arm injured.

- Where in the tropics could an English army doctor have seen much hardship and got his arm injured? = Afghanistan.

Sherlock: Hound of the Baskervilles

- Made a close inspection for the water-mark on the paper

- Held it within a few inches of eyes = Found a faint smell of the scent known as white jessamine.

- The scent suggested the presence of a lady

- There are seventy-five perfumes, which it is very necessary that a criminal expert should be able to distinguish from each other.

Sherlock: The Adventure of Silver Blaze

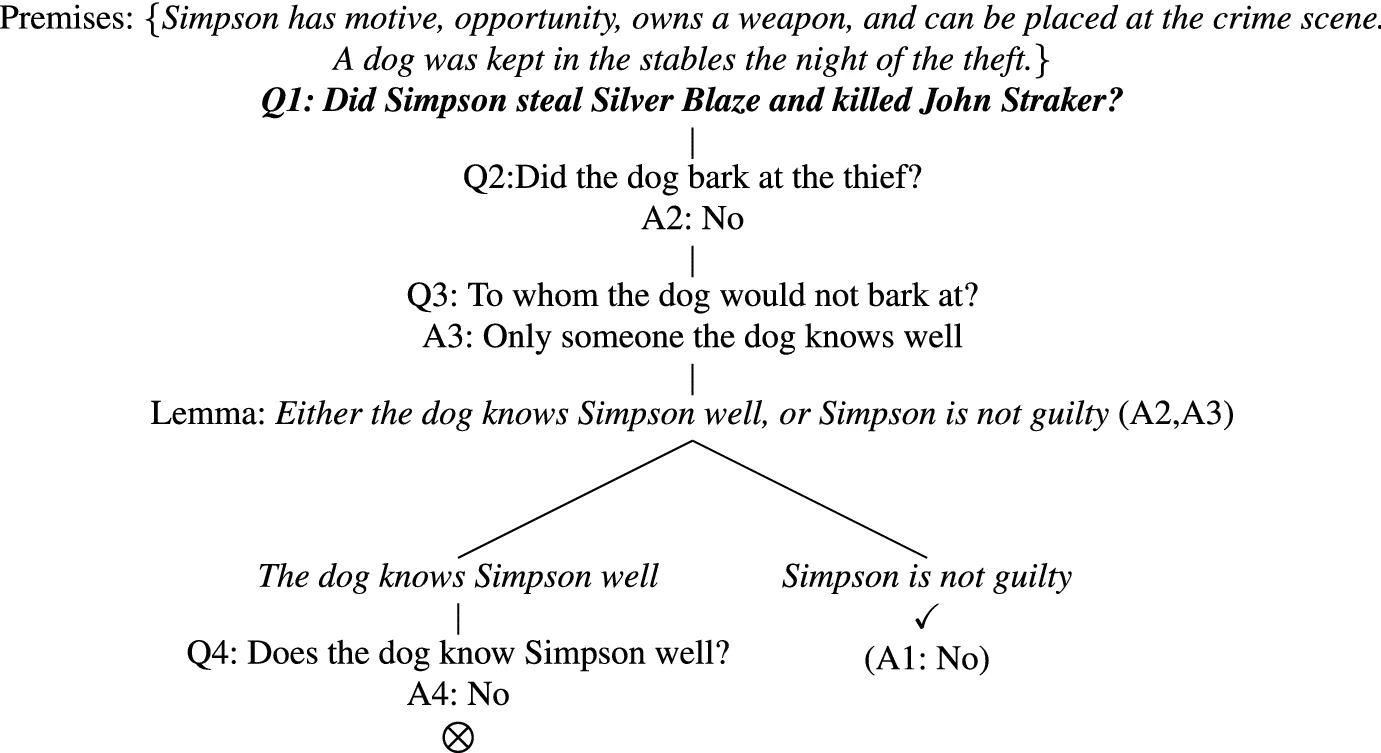

In The Adventure of Silver Blaze, Sherlock Holmes investigates the theft of a racehorse and knows that a watchdog was in the stables at the time of the theft. Sherlock Holmes assumes that a well-trained watchdog would not fail to bark at a stranger. Together with this assumption, one potential answer to the question of whether the dog barked (that it did) entails that the thief was not known to the dog, while the other (that it did not) entails that the thief must have been someone the dog knew well. Entailment is the semantic counterpart of deduction, and so the above amounts to saying that Sherlock selects his question based on what he expects to deduce from its answer, and once obtained, that he deduces that the thief was someone the dog knew well.

A Scandal in Bohemia

In A Scandal in Bohemia, Sherlock Holmes makes two assumptions: that, upon believing that one’s house is on fire, one first check the location of one’s most prized possession; and that Irene Adler’s photograph with the King of Bohemia is her most prized possession. Those two background assumptions together entail that the spot where Irene Adler’s gaze lands immediately after a fire alarm will be the hiding place of the photograph. Again, one could say that Holmes deduced the hiding place of the photograph.

Wigmore Street Post-Office

The following incident, which occurred in his sitting-rooms at 221-B Baker Street, London, will serve to show the distinction that Mr. Sherlock Holmes made in criminal work between observation and deduction. Dr. Watson had carelessly remarked that surely the one to some extent implies the other, whereupon Mr. Holmes sharply replied:

“Why, hardly …. For example, observation shows me that you have been to the Wigmore Street Post-Office this morning, but deduction lets me know that when there you dispatched a telegram.”

Observation:

- A little reddish mould adhering to instep. Just opposite the Wigmore Street Office they have taken up the pavement and thrown up some earth, which lies in such a way that it is difficult to avoid treading in it in entering.

- The earth is of this peculiar reddish tint which is found, as far as I know, nowhere else in the neighborhood.

Deduction:

- I know that you had not written a letter, since I sat opposite to you all morning.

- I see also in your open desk there that you have a sheet of stamps and a thick bundle of postcards.

- What else could you go into the post-office for, then, but to send a wire?

- Eliminate all other factors, and the one which remains must be the truth.”

The Boscombe Valley Mystery

“The murderer,” announced Mr. Sherlock Holmes, “is a tall man, left-handed, limps with the right leg, wears thick-soled shooting-boots and a grey cloak, smokes Indian cigars, uses a cigar holder, and carries a blunt pen-knife in his pocket” There were several other indications of the man, but these would be sufficient, he felt, to start the search which would solve the mystery.

- Length of stride/footsteps as measured from boot prints at the scene of the crime = He is a tall man.

- The right foot was always less distinct = He was lame.

- Struck from immediately behind, yet its mark was on the left side of the body = Left-handed man.

- Cigar ashes found behind a tree and the stub of a cigar, the kind rolled in Rotterdam = Indian variety.

- The tip of the cigar stub had been cut off, not bit off = Use of a pen-knife.

- The cut was not a clean one = Knife must have been dull.

Gloria Scott

“I might suggest that you have gone about in fear of some personal attack within the last twelve months,” began Sherlock Holmes. He then explained that Mr. Trevor Senior had boxed a great deal in his youth, had done some digging in his life, and had been intimately associated with someone whose initials were “J.A.” but whom he now wished to forget.

- The old man carried a handsome cane with melted lead concealed in its head so as to make it a formidable weapon = The fear of an attack

- The man’s ears had that peculiar flattening and thickening = The boxing man

- Many callosities on his hands = A great deal of digging

- In a tattoo, at the bend of his elbow, were the letters “J.A.,” still legible but blurred in appearance, and the staining of the skin around them indicated that efforts had been made to remove them = The desire to forget the person.

The Norwood Builder

The unhappy John Hector McFarlane.

- The untidiness of attire = Bachelor

- The sheaf of legal papers under his arm = Solicitor

- His distinctive watch-charm = Freemason

- His difficulty in breathing = Asthmatic

A Study in Scarlet

- A great blue anchor tattooed on the back of the hand = Sea.

- He had a military carriage, however, and regulation side whiskers = Marine.

- The way in which he held his head and swung his cane = A man with some amount of self-importance and a certain air of command.

- All of these means = A retired sergeant of the Marines.

The Yellow Face

Evidence: A nice old brier with a good long amber stem that had been left behind by a visitor at 221-B Baker Street. Although Mr. Sherlock Holmes had never laid eyes upon the owner of the pipe, he made the following startling deductions about the man simply from observing his pipe:

- Grosvenor mixture at eightpence an ounce, he might get an excellent smoke for half the price = He has no need to practice economy

- The pipe is quite charred down one side = A match could not have done that, the habit of lighting pipe at lamps and gas-jets.

- All on the right side of the pipe = A left-handed man.

- He has bitten through his amber = It takes a muscular, energetic fellow, and one with a good set of teeth

The Sign of Four

Dr. John Watson produced a pocket watch which had recently come into his possession, and he challenged Sherlock to offer some opinions upon the character and habits of the former owner.

- The initials “H.W.” on the back of the watch = the W. suggests Watson.

- The date of the watch is nearly fifty years back, and the initials are as old as the watch = It was made for the last generation.

- Jewelry usually descends to the eldest son + same name as the father + Father has been dead many years = in the hands of the eldest brother.

- The lower part of that watch-case is dented in two places, is cut and marked all over from the habit of keeping other hard objects, such as coins or keys, in the same pocket, a man who treats a fifty-guinea watch so cavalierly = A careless man.

- A man who inherits one article of such value = Pretty well provided for in other respects.

- At least four ticket numbers visible inside of the case = the watch was taken to Pawnbroker at least four times = He had occasional bursts of prosperity, or he could not have redeemed the pledge.

- Thousands of scratches all-round the hole-marks where the key has slipped at the inner plate = He winds it at night, and he leaves these traces of his unsteady hand = Drunkard

- Holmes made the following statements about the former owner of the watch:

- The time-piece had belonged to Watson’s elder brother who had inherited it from his father; the brother was a man of untidy habits-very untidy and careless; he was left with good prospects, but had thrown away his chances, lived for some time in poverty, with occasional short intervals of prosperity; finally, he had taken to drink, and had died.

A Case of Identity

Miss Mary Sutherland is a short-sighted typewriter, she had come away from home that morning in a hurry, she had handwritten a note, using violet ink, before leaving home but after being fully dressed.

- The woman had plush upon her sleeves, which is a most useful material for showing traces.

- Beautifully defined double line a little above the wrist, the person presses wrist against the table – Hand sewing-machine leaves a similar mark, but only on the left arm = Typewriter.

- A dint of a pince-nez at either side of her nose = Short sight and typewriting

- Neatly dressed, but has come away from home with odd boots, half-buttoned = She came away in a hurry

- The right glove was torn at the forefinger, both glove and finger were stained with violet ink = She had written a note before leaving home but after being fully dressed, written in a hurry and dipped her pen too deep. It must have been this morning, or the mark would not remain dear upon the finger.

The Red-Headed League

About the client Mr. Jabez Wilson.

- The right hand was quite a bit larger than his left = Manual labor

- An arc-and compass breastpin = Freemason

- The right cuff was very shiny for five inches, left sleeve contained a smooth patch where the elbow rested upon a desk = Writing

- The tattoo of a fish immediately above his right wrist = Residence in China

- A Chinese coin hanging from a watch chain = Residence in China

- The boots were fastened with an elaborate double bow, not Dr. Watson’s usual method of tying them = who has tied them? A bootmaker – or the boy at the bath. It is unlikely that it is the bootmaker since boots are nearly new. Remains The bath.

- Some splashes on the left sleeve and shoulder of coat = Sat at the side = Had a companion = Shared a cab.

Scandal in Bohemia

Watson was obviously back in medical practice, that he had been getting himself wet lately, and that he had a most clumsy and careless servant girl at home.

- On the inside of the left shoe, just where the firelight strikes it, the leather is scored by six almost parallel cuts. Obviously, they have been caused by someone who has very carelessly scraped round the edges of the sole in order to remove crusted mud from it. = Watson has been out in the vile weather, and that he had a particularly malignant boot-slicing specimen of the London slavey.

- Smelling of iodoform, with a black mark of nitrate of silver upon his right forefinger = Active member of the medical profession.”

- A bulge on the right side of his top-hat to show = Kept his stethoscope

The Crooked Man

- Watson’s boots, although used, are not dirty = When his round is a short one he walks, and when it is a long one he uses a hansom = At present busy enough to justify the hansom.

A Study in Scarlet

- A cab had made two ruts with its wheels close to the curb; up to last night, there had been no rain for a week, so the wheels that left such a deep impression must have been there during the night

- There were also marks from the horse’s hoofs, one of which was dearer than all the others, showing that there was a new shoe.

- Since the cab was there after the rain began, and was not there any time during the morning, it follows that it must have been there during the night, and therefore have brought the two persons to the house.

- Length of his stride = The height of the man

- Wall writing was just over six feet from the ground.” When a man writes on a wall, his instinct leads him to write above the level of his own eyes = The height of the man

- The man avoided a puddle in the garden which was at least four and a half feet across. He had also found square-toed boot prints beside the puddle.

- The writing on the wall had been done with a man’s forefinger dipped in blood = The long finger-nails.

- Some scattered ashes found on the floor = Identified as the dark flaky ash made only by a Trichinopoly.

- Deduction = The victim was poisoned, the murderer was a man. He was more than six feet high, was in the prime of life, had small feet for his height, wore coarse, square-toed boots, and smoked a Trichinopoly cigar. He came here with his victim in a four-wheeled cab, which was drawn by a horse with three old shoes and one new one on his off fore-leg. In all probability, the murderer had a florid face, and the fingernails of his right hand were remarkably long.

It was rare for Mr. Sherlock Holmes to explain in such detail the chain of reasoning behind his deductions, especially to anyone but Dr. Watson, but in this case, he was apparently educating his colleague in the art of observation and analysis.

How to train yourself to think like Sherlock Holmes

- Pay attention to the basics and use all of your senses. A detective begins with the facts of a case before adding in interpretation. Whatever the specific issue, you must define and formulate it in your mind as specifically as possible — and then you must fill it in with past experience and present observation.

- Be ‘actively passive’ when you’re talking to someone. Listening, we have learned, isn’t just a matter of hearing the words people say. Instead, we need to attend the whole of a person’s expression to get all the nonverbal information that’s being communicated — but so easy to ignore.

- Give yourself distance. The pipe smoking is a way for Holmes to constructively distract himself from his thinking. In the same way that playing the violin helps the detective to sort through his thoughts, packing and smoking his pipe does his solution-finding imagination a favor by doing something with his body.

- Say it aloud. Nothing clears up a case so much as stating it to another person. Stating something through, out loud, forces pauses and reflection. It mandates mindfulness. It forces you to consider each premise on its logical merits allows you to slow down your thinking.

- Give Yourself Monthly or Daily Challenges That Force You to Slow Down: Take one interesting picture a day and observe. The idea is to gradually teach yourself to notice small details in your environment and daily life.

- Take Field Notes to Focus Your Attention: First, scientists train their attention, learning to focus on relevant features and disregard those that are less salient. One of the best ways to do this is through the old-fashioned practice of taking field notes: writing descriptions and drawing pictures of what you see. You can do this anywhere. If you’re at work, dedicate 10 minutes to observing one person’s behavior. Pay attention to how often they take a sip of water when their eyes stray from their computer screen, or if they’re constantly checking their email. The more you do this on paper, the better you’ll get at doing it on the fly.

- Power Up Your Deduction Skills with Critical Thinking: Critical thinking is analyzing what you observe closely, and deduction is coming up with a conclusion based on those facts.

- Analyze What You See or Read, and Ask Questions: Form Connections between What You See and What You Know: Holmes remembers so much because he encodes knowledge by seeing its uses right away. It’s similar to how the memory palace works, but instead of leveraging the memory on a space, it connects it to previous knowledge like a mind map. Traditionally, mind maps are used as brainstorming tools, but they’re a great way to take notes as well.

- Increase Your Knowledge Base: You should be broad in your knowledge. Holmes is a walking encyclopedia of knowledge. He reads incredibly broadly—he reads about art, music—things that you would think have no bearing on his detective work. It’s bad to overspecialize, and we should try to remain curious about all the different types of things you want to learn.

It takes a lot of practice and the formation of true habits to emulate the way Sherlock Holmes and other detectives view the world, but it’s not that difficult to do yourself. Once you train your brain to stop and pay attention to the tiny details, the rest of the process falls into place. Before you know it you’re able to analyze any situation—whether it’s a friend’s hangover or a stranger’s affair—in no time.

The limitations of Sherlock like deductive reasoning today

Real science still doesn’t work in the strictly deductive way that Holmes describes, for the best scientific questions, there are no straightforward answers, and a lot of the hard work comes from simply trying to imagine new possibilities. Latent print identification has played a major role in the art of detection. Latent prints include fingerprints, footprints, handprints, animal prints, etc. However, this knowledge of cigar ash, bicycle tracks, handwriting, ciphers, dogs, perfumes, and latent prints hardly matter in today’s modern setting.

Syllogism Modeling Exercise

When creating a syllogism, keep those parameters in mind.

- Major Premise (Use Absolute Fact Not Conjecture)

- Minor Premise (Use Absolute Fact Not Conjecture)

- Conclusion (Sound Logic Used)

It should be noted that syllogisms aren’t perfect. If the major or minor premises are false, you will end up with a conclusion that is faulty. For example:

- Major Premise – Everyone who eats cheese puffs is a computer programmer.

- Minor Premise – Alley eats cheese puffs.

- Conclusion – Therefore, Alley is a computer programmer.

While the argument is valid (the model is being used properly), the logic is not. The logic is faulty because one of our premises are false. When a premise is false, the logic will be faulty. Using truthful premises is paramount to reaching accurate conclusions.

SYLLOGISM CREATOR WORKSHEET

What is a syllogism?

Syllogism is a model used to visualize a form of deductive reasoning logic/reasoning. It contains a major and minor premise, as well as a conclusion. It can be modeled this way:

- All A are B

- All B are C

- Therefore, All C’s are A’s.

To create a syllogism:

First, make a broad statement (major premise). An example of a broad statement would be, “All countertops are made of wood”.

Second, you need to create a linking statement (minor premise) that cites an example of how the first statement is validated. For example, “The Owens own a house with a countertop”. The word “countertop” is the link between the major and minor premises.

Finally, create a conclusion that connects the major and minor premises. Often conclusions are prefaced with the statement, “Therefore”. For example, “Therefore, the Owens countertop is made of wood.”

Now that you know how a syllogism is made, let’s work on creating your own.

Exercise 1 – Create 3 Major Premises

Write four broad statements (major premises). These statements can be true or false. Keep your statements simple. Usually, generalizations are a good starting point for major premises. For example, “all chickens eat worms” or “all sofas are soft”.

Major Premise 1 _______________________________________________________

Major Premise 2 _______________________________________________________

Major Premise 3 _______________________________________________________

Exercise 2 – Create 3 Minor Premises

Write three linking statements (minor premises) to your major premises. Usually, one word will create the link between your major and minor premise. A good way to think of the linking statement is to consider that they are examples of your major premises. For example, “all chickens eat worms” (major premise), can be linked by a specific example, “Sam eats worms” (minor premise).

Minor Premise 1 _______________________________________________________

Minor Premise 2 _______________________________________________________

Minor Premise 3 _______________________________________________________

Exercise 3 – Create 3 Conclusions

Write three conclusions that link your major and minor premises. Start your conclusion with the word “therefore”. The conclusion should come full circle to your major premise. For example, “Since all chickens eat worms, and Sam eats worms, Therefore, Sam is a chicken”.

Conclusion 1 _______________________________________________________

Conclusion 2 _______________________________________________________

Conclusion 3 _______________________________________________________

It might take some time, but the more you practice creating syllogisms, the more you can detect faulty logic and arguments that involve deductive reasoning.

How to train yourself to think like Sherlock Holmes?

1. Pay attention to the basics and use all of your senses.

2. Be ‘actively passive’ when you’re talking to someone.

3. Give yourself distance.

4. Say it aloud.

5. Give yourself daily observation challenges.

6. Take field notes to focus your attentions.

7. Power up your deduction skills with critical thinking.

8. Analyze what you see or read, and ask questions.

9. Increase your knowledge base.How to think like Sherlock?

Pay attention and use all of your senses.

Be ‘actively passive’ when you’re talking to someone.

Say it aloud.

Give yourself daily observation challenges.

Take field notes to focus your attentions.

Power up your deduction skills with critical thinking.

Analyze what you see or read, and ask questions.

Increase your knowledge base.

Read more about the amazing deduction of Ingress 13 Archetype Global Puzzle Challenge. Click here: https://sunnyrabiussunny.com/ingress-decoding-challenge-4-solution/